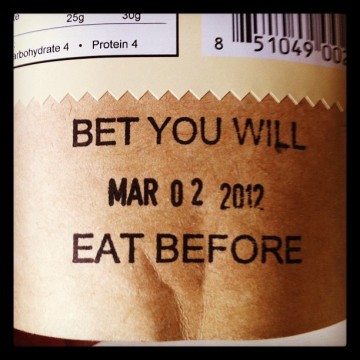

It’s happened to all of us: thirsty, we reach into the refrigerator for a carton of almond milk, only to discover it’s a week past its expiration date. While some might shrug their shoulders, there is a large portion of the U.S. population (me included) that has always taken these labels seriously. If you’re in this camp, listen up: these labels are largely meaningless, and they don’t necessarily indicate a food item’s real point of expiring.

The need to place “best before” or “use by” dates on packaged foods only emerged after a period of major urbanization in the United States, during which there was a decrease in individuals producing their own food (farmers) and an increase in individuals frequenting supermarkets to purchase their foodstuffs. By the 1970s, there was enough consumer uneasiness about a product’s freshness and quality that manufacturers and retailers began to practice what is known as open dating. Instead of affixing a numerical code onto a particular product (called closed dating, which had been practiced up to this point), a month, day, and year were placed prominently on the product so that consumers might feel more confident in their purchases. The problem, however, was that there wasn’t–and still isn’t–a federal law to govern the practice of food labeling, and therefore each state possesses its own standard for how long a food item can be shelved before it is deemed expired.

Labeling inconsistency across states can lead to a tremendous amount of food waste. According to a report by the Natural Resources Defense Council and the Harvard Food Law and Policy Clinic, U.S. food losses are estimated to be 160 billion pounds of food annually. The implications for this amount of food waste are manifold. An overreliance on food labels could cost the average American family $2,275 annually. There are environmental concerns, too: according to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), 34 million metric tons of food scraps were generated in 2010 alone.

The report also discusses the safety concerns surrounding food labels. For many Americans, the “use by” date is the proverbial be-all end-all when it comes to consuming, say, a bag of kale. But experts say that there is no direct correlation between food safety and date labels. However, consumers are unaware of this reality, and as a result, much food is discarded that would otherwise be safe to consume. On the other hand, there is much risk involved in overly relying on these labels. During instances in which the label serves as the only criterion for whether a food is safe to eat, individuals could be putting themselves at risk when not accounting for storage temperatures. For example, setting a block of tofu on the counter top for 24 hours will undoubtedly affect its freshness and safety, even if it has not reached its “use by” date.

Ultimately, it is the responsibility of the consumer to make informed and intelligent decisions when it comes to eating ostensibly expired food. This isn’t a black and white issue: there are many extraneous factors at play and multiple actors involved. As there is no uniform piece of federal legislation to regulate labeling practices in the United States, and the problem of food waste is a serious and pervasive issue in this country, we must all do our part to educate and inform each other when making choices about the food we purchase, consume, and/or discard.

Also by Molly: Why Anyone Can Benefit from Therapy

4 Meal Delivery Services for the Busy Vegan

The Book List: 5 Must-Read Books for Vegans

__

Photo: JP Toto via Flickr