One of the things the coronavirus has made me extremely conscious about is communication. After being isolated and avoiding social interaction for so long (ok so four months, but it feels like longer!), I feel as if any form of in person communication stands out greater to me than it ever did before. Seeing squinted eyes looking at me, which I can only hope to assume are from a masked smile, makes me extremely happy. I even feel as if I appreciate small talk with an acquaintance much more these days as well.

The pandemic hit us when I had just moved countries and was trying to make friends. So it’s no surprise that I’m reveling in small, friendly interactions now that I have the chance to have them again. But during some conversations, I notice that they don’t go anywhere. This is normal in a world where different people have different communication styles. A communication or conversational style is the way we share information through our language. Depending on all the myriad factors that make us who we are, the way we convey thoughts can be abrasive, overwhelming, or aloof-sounding to other people.

The truth is that we’re not going to get along with everyone we meet. But if making connections, getting what we need, or resolving conflicts is something important to us, there are ways to better your communicative approach to make sure you are sending the messages you want to be sending.

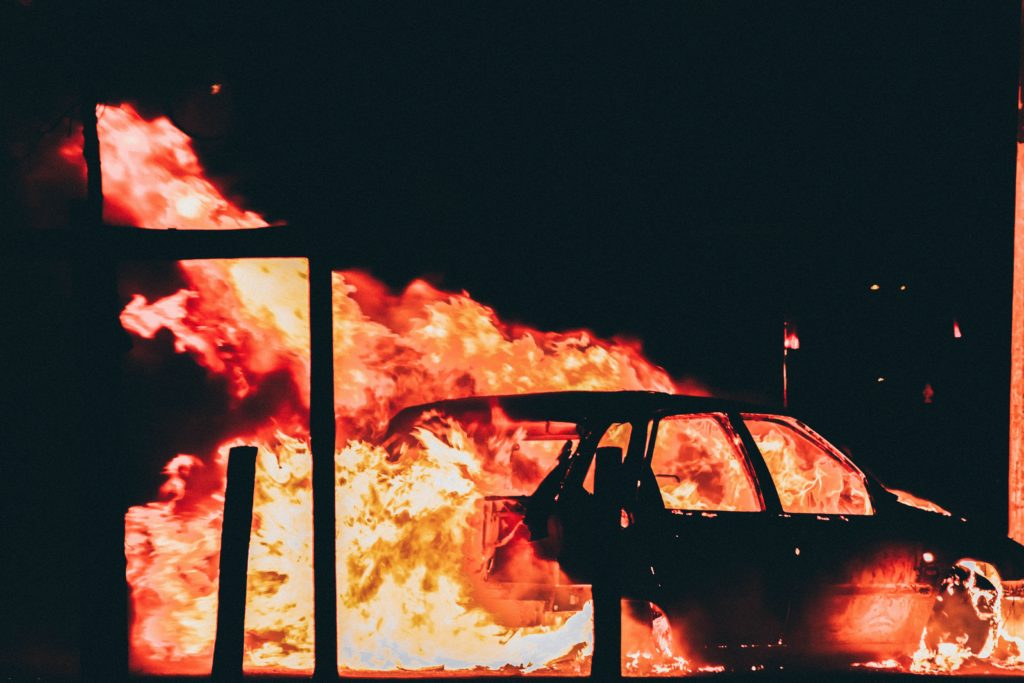

There has been no other time in our generation when improving our communication has been more critical. The protests and riots that have broken out across North America over the last two months are at their base, a form of communication. Stephen Reicher, a professor of social psychology at the University of St. Andrews, writes in “Collective Protest, Rioting and Aggression” that protests “arise out of a crisis of communication,” a discord between what different groups want and need. People are literally screaming out for change, for justice to be served. With this is mind, the way the police have reacted to these protests, both non-violent and violent, is also a form of communication.

In places like Portland, Oregon, non-violent protests have been mixed with rioting (protests where participants have tried to damage civilian or public property, take over public spaces such as police precincts, or act in violence). This has been going on for nearly 60 consecutive nights (at press time). Robert Evans, a conflict reporter who covered wars in Iraq and Ukraine as well as being present at 30 out of the 50 nights of protests in Portland, writes in The New York Times that the riots and police response are about as close to war as we can get, without the use of lethal ammunition. He goes on to say that the tactics the police are using “don’t work.”

The question this specific example poses is: is rioting an effective form of communication? Is it evoking the change that is desired by the protestors? And is the way police are responding (tear gas, rubber bullets, abductions via van) really the best response? If police responded differently, would the riots have ended a lot sooner?

This all circles back to my own personal struggle with effective communication. It made me wonder that if I can research about how to communicate better with those around me, could police officers, too, research about how to interact with protesters in a more proactive manner?

Chief Dan Flynn of the Marietta Police Department has wondered the same thing. In his experience over 40 years in the police department, he has witnessed first hand how a different approach to communication can extinguish conflict and prevent violent riots. In this post, he reveals his involvement in the Georgia G-8 Summit in 2003.

“The G-8 summit had been known to provoke attacks against police, including starting fires and overturning police cars. In preparation for the summit, Flynn’s department called seeking advice from the Calgary police department, the city where the most peaceful G-8 summit to that date was held. The advice they received was that the “key [to a peaceful summit] would be how they communicated with the community.”

This inspired Flynn’s department to create a statement for the summit that both welcomed and advised visitors to behave. The Georgia G-8 Summit turned out to be the best and most peaceful in history.

Simple tips for effective communication

Understand your audience

Know who it is you are talking to. Understanding their background will help you to know where their thoughts and ideas are coming from. It will also help you to choose your words with care as to not offend or make the conversation take a negative turn.

Frame your sentences carefully

Use “I” statements rather than “You” statements. “I feel like you’re not paying attention to me when I speak” is less accusatory than “You never pay attention to me.” “I” statements make the listener feel less resentful because it is about your experience rather than their character. “You” statements imply that the listener is wrong, and casts shame, which is an emotion that arises from feeling bad about one’s own character. Imagine that someone is making you feel bad about your character—you probably won’t be as receptive to their opinion. The key is to create a foundation of mutual respect, rather than mutual shaming.

Find common ground

We are all human, which means underneath it all we want the same things. To be loved, valued, to feel safe, and to be treated equally. Keeping this in mind, ask questions that lead you towards common ground. This can help steer conversations in a proactive direction.

Communicate to accomplish a goal

Keep your goal in mind when starting a conversation. Often, when conversing, different thoughts and feelings come into our brains and can sidetrack the main mission of the conversation. If your conversations veers into something else, be sure to bring it back to your main point, to ensure a meaningful interaction. For example, if your partner concedes that they made a mistake, then don’t list several other instances of their similar infractions.

It’s okay to take a break

Sometimes you or the other person may be too emotionally worked up to carry on a conversation in a respectful, calm manner. In that case, it’s totally okay to say, “I would like to continue this conversation when we are both feeling less charged and when I’ve had the chance to reflect on some of your points. Would that be okay with you?”

Actively and genuinely listen

Listening to someone else is a huge part of effective communication. Even if this person doesn’t share your opinion, you should try to understand their point of view. If you’re trying to convince someone and only speak “at” them, they will likely shut down and become defensive. For example, if you’re talking to someone who loves meat and derides vegans, ask about the thing that they are defending—perhaps it’s that they have fond family memories associated with it. Then you can appreciate the fact that you both have family values, and from there, talk about how strong family bonds are between a mother cow and her calf, and how piglets are separated by iron bars from sows so that they don’t get any physical contact from their mothers. Listening shows your respect for another person’s experiences, which are different from your own; and it gives you a better position to help them see your point of view, too.

Putting these principles into practice

Communication can either spark conversation or extinguish it. Create a hostile environment or a peaceful one. Inspire change or keep things stagnant. The way we interact with others plays a big role in how our lives turn out. This is true across the board, in small ways like making new friends or inspiring change in our society.

Get more like this—Sign up for our daily inspirational newsletter for exclusive content!

__

Photo: Priscilla Du Preez, Davidova, Thain, Hryshchenko, Colas, Olive via Unsplash